Similarities Between Three Major Greek Plagues and the COVID-19 Pandemic

The word “pandemic” is of Greek origin and literally meant “all people” (“pan” meaning “all” and “demos” meaning “people”). That is a fitting etymological origin for a word that has, in just a couple of months, seemingly found its way into the vocabulary of “all people” as the new coronavirus and accompanying COVID-19 disease sweep the earth. However, the word isn’t the only thing that ancient Greece has to contribute to the present conversation about the coronavirus. At least three major plagues are associated with Greek history and tradition--one from the beginning of Homer’s Iliad, one from Sophocles’s tragedy Oedipus Rex, and the Plague of Athens described in Thucydides’s Histories of the Peloponnesian War. Much can be learned from comparing the ancient plagues and the modern coronavirus. In fact, these three plagues from Greek history had remarkably similar effects on their societies as the COVID-19 pandemic is having on society today. The plague from the Iliad engendered anger and rage; the Plague of Athens caused panic; and the plague detailed in Sophocles’s Oedipus Rex led society to petition heaven for relief. The present-day pandemic caused by the new coronavirus has had comparable effects on society.

The Iliad

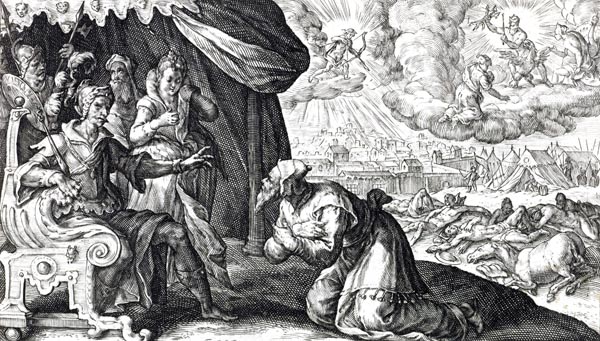

|

| Chryses begs Agamemnon for his daughter, Crispijn van de Passe (I), https://www.poetryintranslation.com/PITBR/Greek/Iliad1.php |

One primary effect of the plague in Homer’s Iliad is anger. The Greeks suffer a plague at the hand of Apollo, who is angry with the Greek leader Agamemnon for taking one of the former’s priest’s daughters as a war spoil. Apollo’s priest, upset with the loss of his daughter, first asks for Agamemnon to return her in return for a ransom payment. When Agamemnon refuses, the priest prays to Apollo, the “Sminthian God of Plague” (Homer 1.47) and asks him to “let the Danaans pay for my tears with your arrows” (Homer 1.51). When the Greeks learn from Calchas the prophet that the way to appease Apollo and stop the plague is to “return the dancing-eyed girl to her father” (Homer 1.104), their first reaction is anger--not gratitude for having received the key to stopping the plague, not remorse for a petty action that caused a pandemic, not initiative to return the girl and restore health, but anger. Before Calchas could even get comfortable in his seat, Agamemnon, “Furious, anger like twin black thunderheads seething / In his lungs” was hurling insults at him and indignantly denying to be left without a war prize. Of course, this violent tirade doesn’t sit well with many of the Greeks, specifically Achilles, whose own fires of rage are stoked by Agamemnon’s sharp words. Were it not for the goddess Athena, who appeared to Achilles to “check this temper of [his]” (Homer 1.21), Achilles may have “scatter[ed] the ranks and gut[ted] Agamemnon” then and there. As it was, he “slammed the scepter” (Homer 1.260) to the ground and withdrew his support from the Greek side. The rest of the work deals with the consequences of Achilles’s rageful decision. The rage of Achilles and spite of Agamemnon can be traced back to the plague, whose main effect on the Greeks was to engender anger.

Similar to the plague described by Homer, the coronavirus plaguing the world now has induced anger in individuals and communities. Dr. Erin Leyba, an individual and marriage therapist from Illinois, writes: “Due to the vast losses associated with coronavirus, many people are experiencing...anger. People may be feeling anger about deep losses related to jobs, finances, normalcy, routines, cherished activities, the health of self or loved ones, or the ability to see friends and family.” She continues, “During the coronavirus pandemic...we are all likely to carry a fair degree of anger” (Leyba). Such plague-induced anger may be to blame for the jump in domestic violence cases reported in many countries worldwide (Berger). Just as in the Iliad, the anger is not directed at the plague itself; rather, the plague serves as a catalyst, angering individuals about other things tangential to it. This anger multiplies the effects of the plague, taking them far beyond the repercussions of the physical disease. One of the main effects that the Iliad’s plague had was angering the Greeks; the COVID-19 pandemic is having a parallel effect.

The Plague of Athens

|

| Plague in an Ancient City, Michiel Sweerts, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plague_of_Athens |

An effect of the Plague of Athens, described in detail by Thucydides in his Histories of the Peloponnesian War, was panic, which manifested itself in various forms. There were false accusations spurred by panic and paranoia: “It first attacked the population in the Piraeus--which was the occasion of their saying that the Peloponnesians had poisoned the cisterns, there being as yet no fountains there” (paragraph 48). Fear of death caused lawlessness to abound: “They saw all alike perishing; and for the last, no one expected to live to be brought to trial for his offences, but each felt that a far severer sentence had been already passed upon them all and hung over their heads, and before this fell it was only reasonable to enjoy life a little” (paragraph 53). Only those who had the disease and recovered were free from the panic--“It was with those who had recovered from the disease that the sick and the dying found most compassion. These knew what it was from experience, and had now no fear for themselves” (paragraph 51)--all others seem to have been gripped by it. To Athens, a powerful and prospering city-state, this was an invisible enemy with an unknown origin and equally unknown solution. It was no respecter of persons--“Strong and weak constitutions proved equally incapable of resistance, all alike being swept away” (paragraph 51). A combination of these factors made panic, at an individual and societal level, one of this plague’s most devastating consequences.

In a like manner, the COVID-19 pandemic promotes panic in individuals and communities. Dr. Judson Brewer, neuroscientist and psychiatrist at Brown University, explains: “Fear is a normal adaptive response, but fear plus uncertainty makes our brains spin out in anxiety…. We can actually catch something that’s even more contagious than a virus--panic and fear” (Meraji). Perhaps no better indicator of the fear and panic sweeping the globe is the hoarding of toilet paper or other goods. Brian Cook of the University of Melbourne hypothesized, “My suspicion is that it is to do with how people react to stress: they want an element of comfort and security” (Abdul-Alim). In other words, the hoarding of toilet paper, more than simply a hygiene-motivated move, is likely evidence that people are stressed, concerned, and fearful of the future, and taking any sort of action to restore security. Just as the Plague of Athens induced fear into the Athenians, the coronavirus has stimulated fear in global citizens today.

Oedipus Rex

|

| Oedipus Separating from Jocasta, Alexandre Cabanel, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jocasta |

A main outcome of the plague penned by Sophocles in Oedipus Rex was that it turned the citizens of Thebes to supernatural beings for assistance. In Oedipus’s first lines, he references the many people sitting at shrines and burning incense in an effort to bring good fortune from the gods (Sophocles 4). The priest mentions “another group wreathed as suppliants / sitting in the marketplace and another / at the double-gated temple of Athena” (Sophocles 20) and later pleads, “May Phoebus who sent these prophecies / come at once as savior and stayer of disease!” (Sophocles 160). The chorus beseeches Zeus, Athena, Artemis, Apollo and Bachus to rid them of the plague caused by Ares (Sophocles 163-216). Each of these incidents demonstrate the Thebans’ reliance on divine beings for support to expunge the plague from among them. The first place that Oedipus sought a solution to the plague was seeking the will of Apollo via Creon. When he needed additional knowledge, he interrogated the blind prophet Tiresias, who “most always sees the same as” Apollo (Sophocles 297). Clearly, the Theban plague turned society to the supernatural to seek healing.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had an identical effect on the global community. In a study conducted by Pew Research Center, one quarter of Americans reported that their own religious faith has become stronger as a result of the coronavirus outbreak (Gecewicz). Among Christians, that number was over one third. Only two percent of all Americans stated that their faith has become weaker as a result of the pandemic. Millions of people worldwide participated in a fast for relief from the present-day plague on Good Friday, April 10. A Facebook group titled “Worldwide Fast April 10” amassed over five hundred thousand followers, as religious and non-religious people alike combined efforts in calling upon God for healing, protection, and revitalization. Just as the Theban plague, COVID-19 turned society to the supernatural for relief.

Each of these three major plagues in Greek history and tradition had similar effects on their respective societies as the modern COVID-19 pandemic has had on society today. Just as the plague recounted in Homer’s Iliad engendered anger in its community, so too the present pandemic. Both the Plague of Athens described by Thucydides as well as the coronavirus induced panic and fear on an individual and societal level. The ancient Thebans relied heavily on their gods to rid themselves of their plague, a behavior emulated by people worldwide during the COVID-19 contagion. The common thread that runs through all four plagues? Each came to, or will yet come to, an end. As we look to the past to learn and compare, let us also look to that future day with hope in our hearts, praying that when that end comes, we will be better as individuals and communities because of the experience.

Works Cited

Abdul-Alim, Jamaal S. “Why Are People Stockpiling Toilet Paper? We Asked Four Experts.” The Conversation, The Conversation US, Inc., 20 Apr. 2020.

Berger, Miriam. “Measures to Control the Spread of Coronavirus Are a Nightmare for Victims of Domestic Violence. Advocates Are Demanding Governments Step up.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 1 Apr. 2020.

Finley, M. I. The Portable Greek Historians : The Essence of Herodotus, Thucydides, Xenophon, Polybius. Penguin Books, 1977. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=1127501&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

Gecewicz, Claire. “Few Americans Say Their House of Worship Is Open, but a Quarter Say Their Faith Has Grown Amid Pandemic.” Pew Research Center, Pew Research Center, 30 Apr. 2020.

Homer. Essential Homer, Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., 2000. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/byu/detail.action?docID=473607.

Leyba, Erin. “When Anger From Coronavirus Is Displaced.” Psychology Today, Sussex Publishers, 3 Apr. 2020.

Meraji, Shereen Marisol. “Coronavirus Panic: How To Get Your Thinking Brain Back Online.” NPR, NPR, 16 Apr. 2020.

Sophocles. Oedipus Rex. Translated by J. E. Thomas, Prestwick House, 2005.

Comments

Post a Comment